By Barry Lopez

This essay to commemorate the 50th Anniversary of the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act first appeared in Patagonia November 2018 Journal. It was reprinted here with the author’s permission.

Within 24 hours of noon on September 17, in any given year, spring chinook salmon arrive on gravel bars in front of my home to spawn. The females dig their redds, the males fertilize the eggs, and then both breathe their last. I’ve watched this event for 48 consecutive years on the middle reach of the McKenzie River in western Oregon. Each year I wait for the reassurance they bring, that even though things abstract and concrete are looking bad everywhere in the world, these fish are carrying on. If the salmon don’t arrive by the evening of the 17th, I walk down through the woods to stand in the dark and listen for them. I know most all the sounds this river makes, and there is no other sound like their caudal fins breaking the surface of the water as they mill. If I hear them, then I know things are good for this particular strain of salmon for at least another three years. If I don’t hear them, I toss and turn through a sleepless night and go down to look first thing in the morning.

They always arrive. I’ve never had to wait more than a few hours.

Much of what I know about integrity, constancy, power and nobility I’ve learned from this river, just as I’ve learned the opposite of these things—impotency, fecklessness, imprisonment—by walking across the dam on Blue River, a tributary of the McKenzie, and by standing on Cougar Dam on the river’s South Fork, another tributary. I stare at the reservoirs from the tops of these dams and see the stillness of the impoundments. The absence of freedom there.

I couldn’t say that I knew the McKenzie after my first year here. I had to nearly drown in it once, trying to swim across from bank to bank one day and dangerously misjudging the strength of the river’s flow. I had to watch a black bear wade through a patch of redds, biting through the spines of the adults. I had to come into the habit of walking its stony bed upstream and downstream, in daylight and at midnight, bracing myself with a hiker’s pole and calculating each slippery step, the water vibrating the pole in my hand like a bowstring and breaking hard over my thighs. I had to see how the surface of the river changed during a rainstorm, with the peening rain filling in the troughs and hammering down the crests. I had to become more than just acquainted with the phenomenon. I had to study beaver felling alders in its back eddies, great blue herons stab-fishing its shallows and lunging otters snatching its cutthroat trout. I had to understand the violet-green swallow swooping through rising hatches, and the ouzel flying blind through a water-fall. I had to watch elk swimming in the river at dusk. But still, I can’t say I know it.

As I showed continuing interest in the McKenzie over the years, the river opened up for me. I began to feel toward it as I would a person. I learned that it had emotions and moods as subtle as any animal’s. And I learned that, in some strange way, the river had become a part of me. When I was away traveling I missed it, the way you miss a close friend.

The first river I developed any strong feeling for was a stretch of the Snake that winds through Jackson Hole. In 1965 I was working a summer there in Wyoming, wrangling horses and packing people into the Teton Wilderness. Some afternoons when I was free I volunteered as a swamper on float trips, eager to get a feeling for the undulation of that water. Since then I’ve been able to float the Middle Fork of the Salmon in Idaho, the Colorado through the Grand Canyon, the upper Yukon in Alaska and the Green in Utah, gaining from them experience with more formidable water. I’ve since seen rivers far from home, like the Urubamba in Peru, perhaps the wildest river, in terms of its miles of continuous commotion, that I’ve ever stood before. And I visited some way-far-off rivers like the Onyx, a name that brings a wrinkled brow to every river rat I’ve ever mentioned it to.

The Onyx, Antarctica’s largest river, flows for only a few months in the austral summer, from the base of the Wright Lower Glacier in the Wright Valley to perennially frozen Lake Vanda. During a week I spent there once, at New Zealand’s Vanda Station on the shore of the lake, I decided to hike a few miles of the river’s north bank, wishing keenly all the while that I had a kayak. The Onyx is about 30 feet across and a foot deep, and it runs flat. A little bit of experience with the Onyx, though, helps you grasp the breadth of meaning behind the term “wild river.” The designation includes everything from the virtually unrunnable, like the Urubamba, to pristine but tame rivers, like the Onyx. I’ve also spent time in the thrall of another, singular type of wild river—ones that are perfectly runnable but that have gone, in my lifetime, from being virtually unknown to being popular destinations.

In the boreal summer of 1979, I was camped on the upper Utukok River, on the north slope of the Brooks Range in western Alaska. A wolf pack denning in a cutbank there interested my friend Bob Stephenson, a wolf biologist with the Alaska Department of Fish and Game, and me. We’d set up our tent on a rise on the opposite side of the river, about 500 yards away. During the week we spent there, we not only saw no person except the bush pilot who brought us in, but also no evidence of anything from the man-made world. A tundra grizzly had torn up a ground squirrel’s burrow 20 yards from the tent just before we arrived. We watched wolves hunting every day. We saw gyrfalcons, snow buntings, horned larks and jaegers on their nests. One night, 30 or so caribou crossed the river in front of us at a run, throwing up great sheets of water—diamonds backlit by a late-night sun.

When Bob died last year, we held a memorial service for him in Fairbanks, and I caught up with a retired biologist I’d known at the department who told me that commercial float trips now take people regularly down the Utukok. It’s certainly a wild river, providing an unforgettable experience for adventurers, some of whom have become river activists as a result. To my way of thinking, however, the Utukok is not so wild now as it was when we were camped there 40 years ago, when the country, for as far as you could see, belonged to the animals.

Home from some trip and back here on the banks of the McKenzie, I always feel that I’ve come back together again as a person. In spring, when I notice the first few flowers blooming in the riparian zone—trillium, yellow violet, purple grouse flower, deer’s head orchid—I’m aware of similar changes in myself. I’ve lived here long enough now—intimate with the McKenzie’s low- and high- water stages, its winter colors, its harlequin ducks, its log jams, and aerial plankton (tens of thousands of spiders “balloon drifting” in summer on breezes above the river)—to know that without this river I’m less. Listening to osprey strike the river, watching common mergansers shooting past me at 60 miles an hour, a foot off the water, hearing the surging wind roiling the leaves of black cottonwoods close around me, I become whole again.

Many people, I have to think, have wilder and more inspiring stories to tell than I do about illuminating and staggering moments spent with a wild river. I have to believe, though, that we all share equally a love for the great range of expression this particular kind of being offers us, whether we’re with it in the moment or must call up remembered feelings from former encounters. And, of course, today we all share a fate with them, during these days of the Sixth Extinction; and we know how late it is in human history to finally be thinking about protecting rivers.

We’re only just now getting started with it. Congress passed the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act in 1968, 50 years ago this year. The bill was designed to protect eight different rivers from development—among them, the Middle Fork of the Clearwater in Idaho, the Eleven Point in Missouri and the Middle Fork of the Feather in California. In 1988, after another 27 rivers had slowly been incorporated into the system, Oregon passed an omnibus river bill that added another 40 rivers, including the McKenzie, each one with designated stretches of “wild,” “scenic” and “recreational” water, and each one of these sections subject to increasingly stricter levels of management. Today, there are 208 wild and scenic rivers across 40 states—12,743 miles of protected river water. It’s a paltry sum, actually, less than a quarter of 1 percent of the nation’s river miles. But each year our understanding of the nature of this kind of planetary lifeblood grows deeper. As more land trusts come into being, like the McKenzie River Trust here, the number of champions and custodians grows larger.

Over the years, I’ve learned much about the McKenzie that is obvious and much that is subtle. On this waterway that supplies the city of Eugene with virtually all of its drinking water, for example, state and federal agencies have cooperated to protect bull trout and to restore the spring chinook salmon run on the upper South Fork of the river. And for subtlety, I would offer you obsidian tools buried in the river’s riparian zone, evidence I’ve found of the very early presence of people here, some of it from before the days of the historic occupants, the Kalapuya and Molalla, tribes who traveled to the upper McKenzie in the summer to gather a great profusion of berries—blackberries, salmonberries, huckleberries, elderberries, osoberries and thimbleberries (all of which remain a priority today for local residents and others to gather).

The goal for most of us on the McKenzie today is not simply to protect the physical river from miscreants by implementing various layers of necessary regulation from ridgeline to ridgeline, but to revitalize and protect the entire community associated with the river. To help all who are interested understand that this river began its life long before human beings arrived, and that the wildness it offers us all can still be accessed, engaged and offered to our children. We’re living today, of course, in a time of true political, social and environmental upheaval and growing threat. You can select living creatures like rivers, if you choose, and take your stand with them to ensure your own future and the future of other beings. It’s a good place to be with your friends and your family, as the growing shadows blanket our skies.

On September 17, 2018, I will go down to the river and wait. I will watch for sun-light gleaming on the salmon’s caudal fins, standing proud of the surface of the water in the river’s shallows. I will smell them on the evening air and watch the males converge on the females, shouldering each other out of the way. And I will concentrate on this thought: If I do not help them to keep doing this, my days too are numbered.

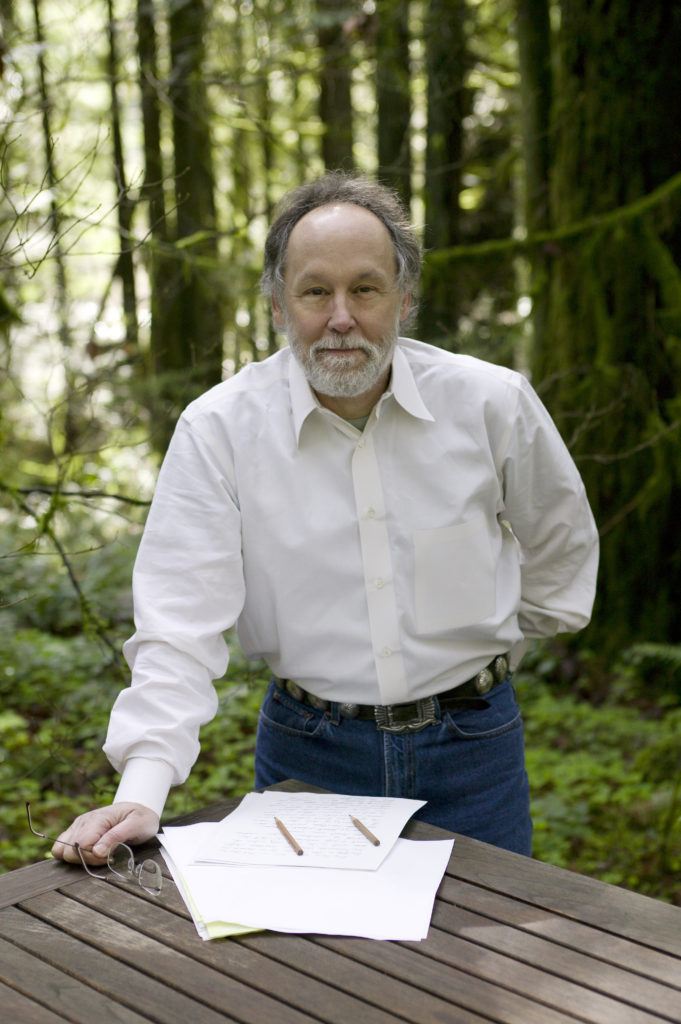

About Barry Lopez

Barry Lopez was a 51-year resident of the McKenzie River Watershed until his death in December, 2020. He was the author of Arctic Dreams, which won the National Book Award, and over a dozen other works of fiction and nonfiction. A collection of essays, Embrace Fearlessly the Burning World, was released by Random House in May 2022. He was a dear friend to McKenzie River Trust and served as the honorary chair of our McKenzie Homewaters Campaign.