As a semi-truck speeds by at over 60 miles per hour, it’s hard to ignore the contrast between the modern highway and the ancient fish being carefully moved from tank to barrel. Pulled over on a narrow shoulder next to the Oregon Country Fair site on Highway 126, a group of fisheries scientists from the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation (CTUIR) and the Nez Perce Tribe are busy collecting DNA samples from Pacific lamprey (Entosphenus tridentatus). Just a few hundred yards downstream, these fish will be released into the Long Tom River, where they haven’t been seen in nearly a century.

Standing in the bed of a large white truck equipped with a special transfer tank, Jerrid Weaskus (Nez Perce Tribe) dips a long-handled net into the water and slowly draws it forward and backward. Suddenly, half a dozen squirming bodies lift through the air and are transferred into a 35-gallon barrel where they can be counted and sampled for DNA before being released.

These fish are part of a decades-long effort to restore Pacific lamprey populations in the greater Columbia River watershed. Spearheaded by the Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission, which was established in 1977 to unify fish protection efforts of the Confederated Tribes and Bands of the Yakama Nation, the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation, the Confederated Tribes of the Warm Springs Reservation of Oregon, and the Nez Perce Tribe, today’s lamprey release marks and important moment for the expansion of Tribal-led lamprey restoration efforts into the Long Tom watershed.

“I’ve been working on this project since the 1990s,” explains Weaskus, “so I can tell you from my own eyes that these efforts make a difference.” Since 2000, lamprey returns in the Umatilla River, the first site of relocation efforts, have improved from years with a handful of returning fish to a single season high of 4,500 adult spawners in 2018.

Aaron Jackson (Walla Walla), CTUIR Pacific Lamprey Project Leader explains how the program got started: “Back in the late 80s to early 90s, Tribal members were warning about declining lamprey populations, but no one outside Tribal communities was motivated to protect this fish that doesn’t have the appeal or economic value of commercial fish like salmon. Because of this, the Tribes had to be the ones to step forward and search for solutions.”

Rising to the need, leaders from the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation developed and implemented an experimental plan to restore lamprey by physically moving adult fish from mainstem rivers and placing them above dams. This technique, called translocation, is now being used in the upper Long Tom Watershed, where Pacific lamprey once lived but haven’t been seen in decades.

A River's Lifeline

With fossil records dating back more than 450 million years, lamprey species have existed in Earth’s waters longer than our imaginations can reach. Despite predating humans, whales, dinosaurs, and even the supercontinent Pangaea, the animals have undergone few physical changes over the millennia. Emerging alongside Earth’s first primitive forests, lamprey established an early link between land and sea, which they have maintained since time immemorial.

Pacific lamprey are a lifeline for northwest river ecosystems and throughout their lifecycle, they take care of the waters they call home. Lamprey are born in freshwater and live as larvae (also called ammocoetes) buried in sediment for several years. During this time, they feed on debris, filtering nutrients and cleaning the riverbed. “It’s pretty incredible,” says Jon Hess, a senior fisheries geneticist with the Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission. “All throughout our river systems, thousands of young lamprey are burrowed deep in sediments, working unnoticed to keep our rivers healthy.”

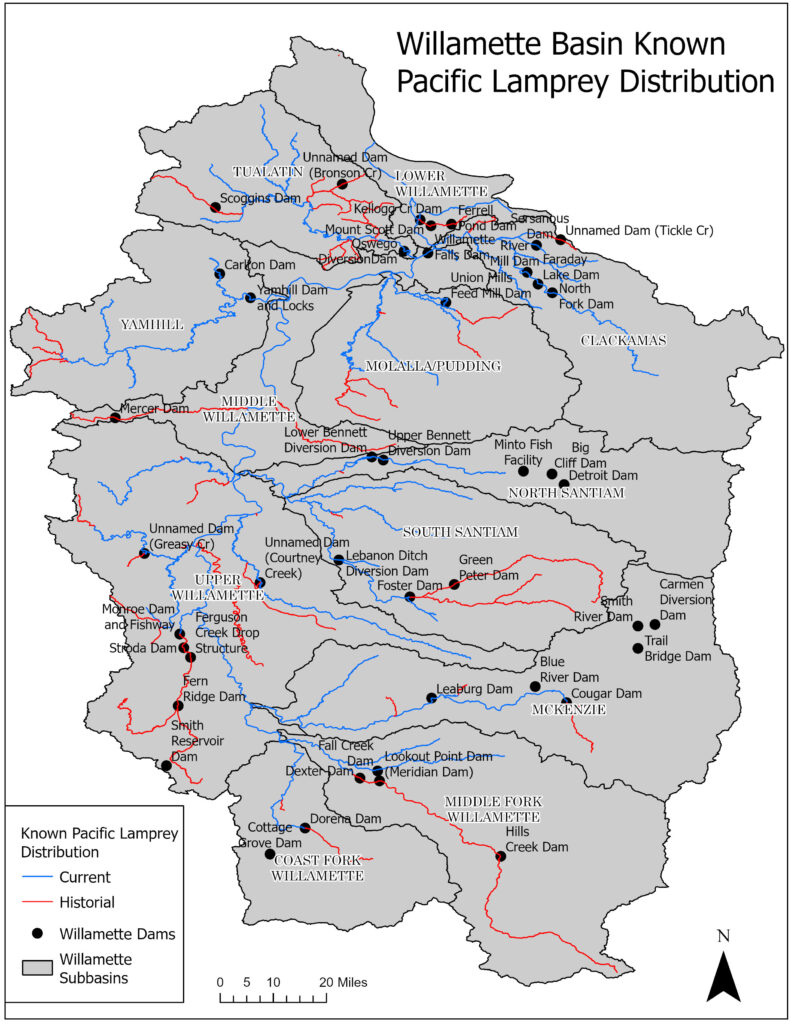

Young lamprey rely on calm areas like side channels and oxbows for food and shelter, but in the Willamette River system, these river-adjacent areas have been drastically reduced. In the Upper Willamette River (Eugene to Albany), over 70% of side channels were lost between 1850 and 1995 as the river was straightened and deepened for navigation by boat, making the protection of remaining areas critical for the long-term survival of this special species.

Following their years in the sediment, larvae grow into juveniles (also called macrophages) and journey to the Pacific Ocean, where they undergo one final transformation into their adult form and spend two to seven years feeding before returning to freshwater to spawn.

“It will be especially exciting when we find a few of these kids coming back to Willamette Falls as adult spawners,” exclaims Hess, who anticipates the earliest returning adults will appear around 2034. But lamprey don’t follow the same patterns as other migratory fish like salmon, and two to seven years is a broad time window to predict when they might return. Because of this, tracking success requires a different approach.

Tracking Recovery

The work in the Long Tom watershed is part of a larger, Tribal-led effort to implement the recently updated Tribal Pacific Lamprey Restoration Plan for the Columbia River Basin. This work builds on years of learning and action taken by the four Columbia River Treaty Tribes to preserve and enhance Pacific lamprey populations, including through translocation.

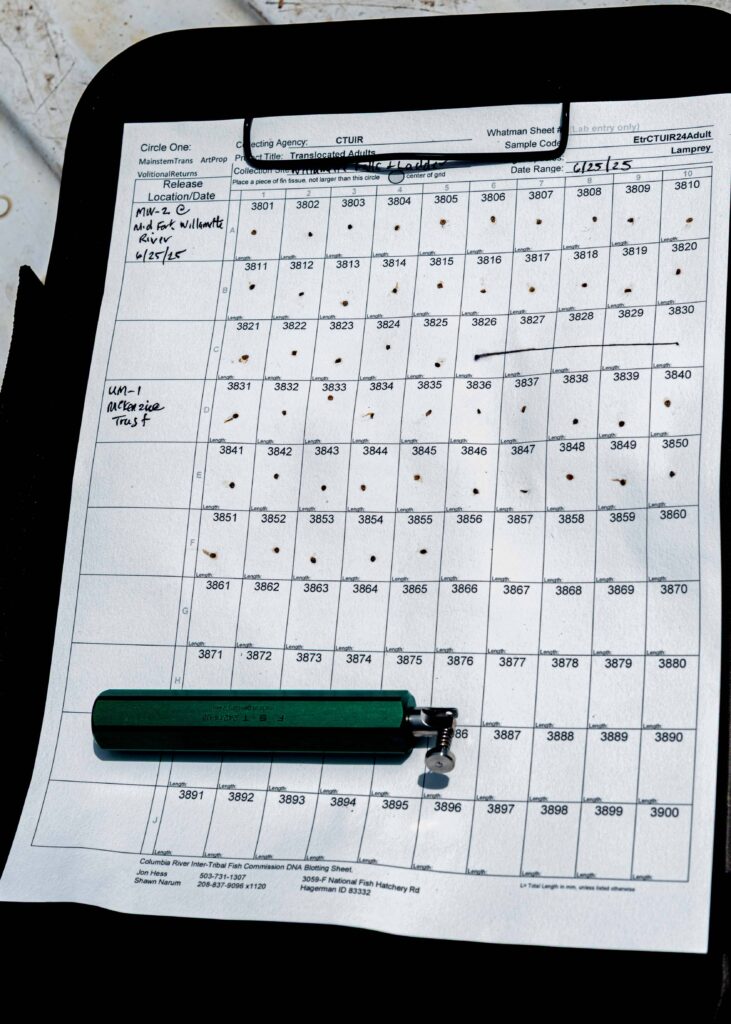

Over the past 25 years, more than 70,000 adult lamprey have been translocated in the system, and in 2025, 17,000 were collected from Columbia River dams to support translocation programs. Once collected, adult lamprey are moved to rivers and streams in Oregon, Washington, or Idaho that they can no longer reach due to dams and other in-stream impediments. Before the fish are released, staff take a DNA sample from each fish to help track their success.

“Because their lifecycles are so varied between watersheds and individuals, we can’t just count returning adults,” clarifies Jackson. “DNA research is needed to measure whether these lamprey are spawning successfully and establishing new populations.”

After lamprey are returned to a section of river, researchers will return to survey for larvae in sediments near release sites, and the presence of young larvae is a welcome sign for researchers and fish. “Lamprey are unique in that they don’t always spawn in the streams they come from,” explains Jed Kaul, a fish biologist with the Long Tom Watershed Council. “Returning adult lamprey can smell the pheromones of upstream larvae, and if they smell young fish upstream, they know it’s a good place to raise their own, so future lamprey will be attracted back to these areas.”

To sufficiently understand the impact of restoration efforts, a biologist also monitors and collects DNA samples from returning fish at Willamette Falls, an area that all Pacific lamprey must pass through to reach the middle and upper Willamette watershed. “The samples we collect can tell us which lamprey are siblings and who their parents were,” explains Hess. “With this information, we can track where they were born and understand where our efforts have succeeded.”

If the new lamprey population in the Long Tom takes hold, young fish from these releases may start migrating to the ocean around 2030—and some could return as adults as early as 2034.

Breaking Barriers

Returning lamprey to the upper Long Tom watershed is just the beginning. Dams still block their way upstream, cutting off their historic habitat. That’s why the Long Tom Watershed Council has spent over a decade working to improve fish passage at three outdated dams on the Long Tom River. “These 9-to-12-foot structures are obstacles for migrating fish,” explains Kaul. “Depending on water levels, they can completely block passage.”

The furthest downstream dam is located in Monroe, where the Council has been leading a multi-year effort with the City of Monroe, the Confederated Tribes of Siletz Indians, and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) to develop a plan to remove the dam. Thanks to support from USACE, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and other agencies, the Monroe dam is now on track to be removed within two years, well before the projected return of adult lamprey. Looking upstream, partners are already busy exploring solutions for the next two river impediments.

Once these barriers are removed or mitigated, over 100 miles of the Long Tom River and its tributaries could be accessible to migratory fish for the first time in nearly a century. While Fern Ridge Dam still blocks the upper watershed, Kaul is hopeful: “If lamprey get established upstream, it could open the door to building passage at Fern Ridge. This effort to restore lamprey in our watershed demonstrates that our daily work to improve watershed health for our community and support the plants and animals who call this place home matters for the long run.”

A Cultural Connection

Just upstream at Coyote Spencer Wetlands near Crow, Oregon, partners gathered earlier in the morning to welcome lamprey back to Coyote and Spencer Creeks. The 225-acre conservation site is owned by McKenzie River Trust and co-managed with the Long Tom Watershed Council and the Traditional Ecological Inquiry Program (TEIP). TEIP works with Native youth and families, helping young people reclaim Indigenous science and ecological knowledge.

Lamprey play an important cultural role for Indigenous communities across the Pacific Northwest and are deeply woven into Tribal culture. While each band and tribe has unique relationships with lamprey, all agree that safeguarding these ancient fish for future generations is our responsibility today.

During introductions, Sage Hatch (Siletz), a TEIP educator, explains, “I grew up fishing for lamprey. I grew up eating lamprey. Lamprey have always been part of my life and culture. I’m here because this fish matters to me and my family.”

Through the Traditional Ecological Inquiry Program, youth work alongside landowners, agencies, and stewardship partners, including Pacific lamprey, doing restoration work in the Long Tom and other regional watersheds. They take on leadership roles in hands-on projects that focus on healing the land through learning about “good fire,” clean water, healthy soil, and fresh air. “All of these activities help restore our shared landscape,” says Joe Scott (Siletz), curriculum director for the program. “In addition to the clean water needed to support Pacific lamprey, the meadows here also hold large populations of camas and other first foods that are gathered and tended by TEIP’s interns and families.”

At Coyote Spencer Wetlands and nearby lands, Tribally-led cultural burns are also helping restore native prairies and wetlands. The fires help to reinvigorate native plants and improve soil health, which in turn contributes to cleaner water in nearby creeks. “This kind of full-ecosystem approach respects the role of every relative in the landscape, including the plants and animals that have sustained Tribal people since time immemorial,” says Scott. “Welcoming lamprey back shows youth that our culture is alive and that they have an important role as caretakers of this place.”

A Quiet Return

Back along Highway 126, the team carefully moves twenty-five fish from tank to net. Following a quick DNA sample, their one hundred and fifty-mile journey from Willamette Falls to these new waters is over.

After a short scramble down a steep embankment, the squirming net is gently lowered and emptied into the Long Tom River. As bodies reunite with water, lamprey burst in all directions like ribbons unwinding in the current. The fish dart up and downstream, slip between boulders, and disappear.

As the last of this year’s cohort disperses, it’s difficult not to wonder if this ancient fish, which has persisted for millions of years, will be able to endure the next hundred to come. Navigating back up to the highway and into the hum of modern life, the questions linger: How did we get here? Will this be enough? The past has left deep scars on these rivers and the species and cultures fastened to them. Yet the return of the lamprey offers a glimpse of what’s possible when people commit to repair, not just remember.

As the truck pulls away and the river fades behind, a quiet sense of gratitude settles in. Gratitude for the lamprey, their endurance across time, their care for our rivers, and the people who never stopped fighting for them.

Even as traffic thunders overhead, these ancient fish move upstream, steady, unseen, and determined. They remind us that healing is slow but possible and that the choices we make now will ripple forward, shaping the future of our rivers, our communities, and the species that depend on them for generations to come.

Learn more about the people leading these projects!

The Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission coordinates management policy and provides fisheries technical services for the Yakama, Warm Springs, Umatilla, and Nez Perce tribes.

CRITFC’s mission is “to ensure a unified voice in the overall management of the fishery resources, and as managers, to protect reserved treaty rights through the exercise of the inherent sovereign powers of the tribes.”

For 25 years The Long Tom Watershed Council has worked on behalf of its community to build a culture of neighbors helping neighbors to do the right thing for land & water in the home we share. From the Coast Range to the Willamette River and everything in between, this community expresses its values for clean water and healthy habitats through the council’s work – watershed wide. Explore our new website and discover the high-impact projects and programs that benefit everyone who calls the Long Tom home.