By Garrett Reagan – Outreach and Communications Intern

McKenzie River Trust and our partners at the Long Tom Watershed Council are working to restore critical oak and prairie habitat in the Long Tom Watershed. Coyote Spencer Wetlands is a 191-acre property at the confluence of Coyote and Spencer creeks in the Long Tom Watershed. This protected area provides important refuge for numerous oak-dependent species. Coyote Spencer Wetlands boasts 145 native plant species including camas, suncups, thin-leaved Peavine, and the rare Oregon larkspur, making restoration of this oak and prairie wetland a critical investment in species health and diversity. On-the-ground work happening this summer is the first step in a 10-year restoration plan co-developed with our partners at the Long Tom Watershed Council. This ambitious plan will help to care for and restore one of Oregon’s most rapidly declining habitats.

Maintaining oak savanna and prairie habitats plays a key role in species conservation and ecological reinvigoration. In the Willamette Valley, less than 3% of oak savanna and less than 7% of oak woodlands remain. Suppression of fire regimes (intentional burning by Indigenous communities), woody vegetation encroachment, and competition from nonnative plant species all pose threats to the health of oak, prairie, and riparian ecosystems. Without restoration actions, rare habitats and rare species will likely continue to decline. Restoration in places like Coyote Spencer Wetlands buffers the plant and animal communities that depend on these ecosystems against the ongoing impacts of environmental degradation.

Oregon’s lands and rivers are all disturbance-dependent, meaning that they have evolved since time immemorial with flood and fire. With a lack of disturbance in oak woodlands, savannas, and prairies, an increasing number of plants have not been recycled back into the soil. Restoration work at Coyote Spencer Wetlands aims to halt the encroachment of various plants, both native and non-native, creating space for more sensitive species to reclaim the ground. Thinning the trees in this area supports both oak tree crowning, and native understory composition.

Historically, Indigenous communities in the American west have used fire to manage oak savanna and prairie ecosystems. Alongside supporting the care of culturally important foods and fibers, this technique also reduces underbrush competition for more sensitive, low-growing plants. The unique plant communities declining across oak and prairie habitats rely on this regular disturbance for survival. Part of the restoration plan includes working with tribal partners to return good fire to this landscape, building on collaborative efforts across the region to reintroduce fire to the landscape under tribal leadership.

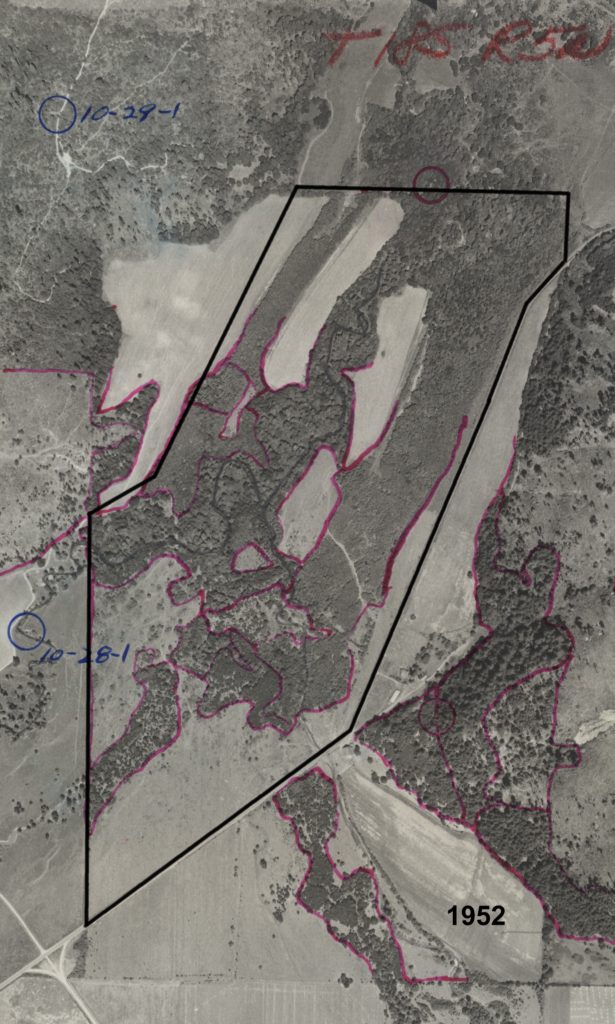

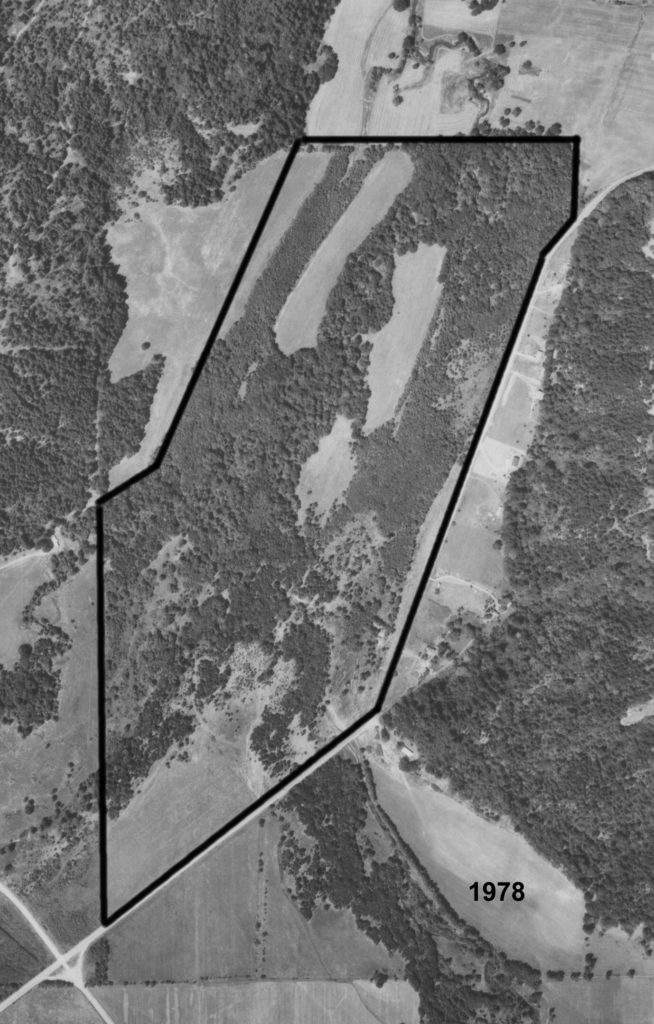

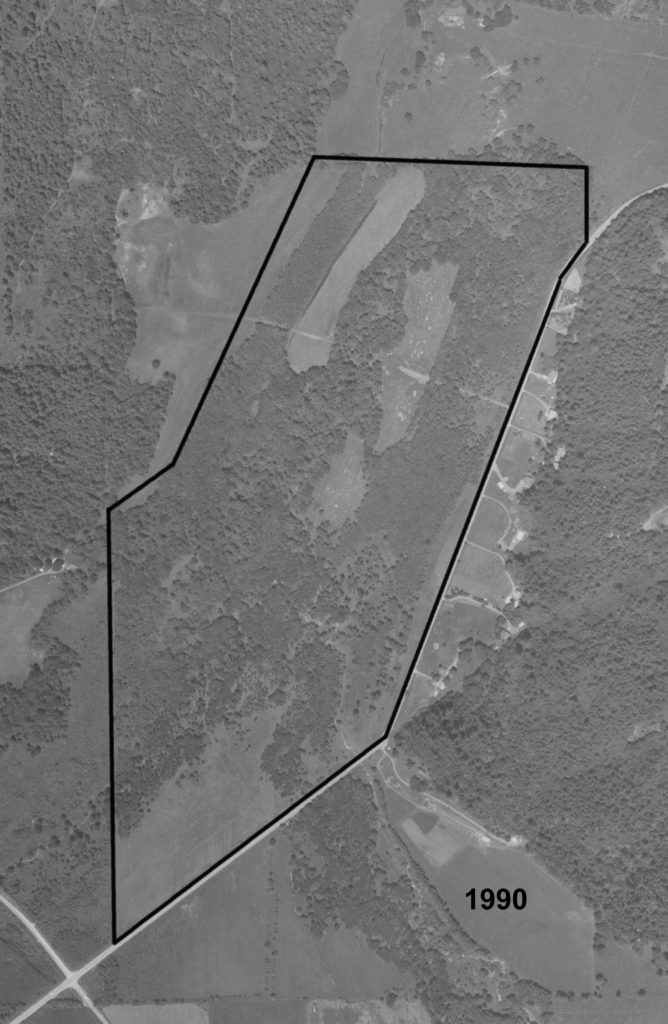

Cultural burning practices were banned in the Willamette Valley, and much of the western United States, by 1850. Since that time, forests, wetlands, and prairies have changed dramatically in their vegetative makeup. These impacts were not fully captured until the advent and availability of planes to take aerial photos. In the Willamette Valley, historic photos became more available beginning in the 1930s, providing a window through time to a different landscape view. Utilizing historic images and vegetation data helps us see changes in landscape patterns and ecosystems over time. In combination with the current site conditions and long-term management planning, this data helps to inform habitat restoration objectives as we work to support species diversity across the landscape.

Each unique habitat that we work in presents its own diverse set of needs. Restoration work at Coyote Spencer Wetlands aims to nurture the landscape and promote habitat resilience for multiple threatened and endangered species. Taking action including implementing prescribed burns, thinning encroaching tree species, and removing Oregon Ash from wetland areas will improve soil moisture, increase sunlight exposure, reduce species competition, and enhance overall species composition. From thinning out the overgrowth of trees and shrubs to working with partners on returning fire to the landscape, investments in oak and prairie restoration present an incredible opportunity for us to leave the land better than we found it.

Historic aerial photos offer key reference points for successful land management techniques and better visualize the impacts of fire suppression policies on a landscape scale. Above, a series of historic images show the encroachment of ash trees in the lower left-hand wetlands known as the Bloomer Complex. Restoration work at Coyote Spencer Wetlands focuses on restoring those wetlands to open wet prairie habitat.